Hesston College students saw how different education can be from one place to another after spending a day in a Tulsa, Okla., high school.

Hesston education professor Marissa King took a group of 24 education majors to Central Junior High and High School Feb. 14 to experience a school that, for most of her students, was a new environment.

“I want my students to have tangible experiences, to explore their interests and build skills,” said King. “For many students, this trip was cross cultural. We were looking at a school that is incredibly diverse and in an urban setting. The problems and issues are much different than those an affluent school may face.”

Hesston students are used to observing in classrooms in the fairly affluent and rural school districts of Harvey County, Kansas, and most of them come from similar educational experiences. Central provided an opportunity to see education at work in a low economic, inner-city area where school is often not a top priority.

Central is classified as a Title I, Needs Improvement School because it has failed to meet the requirements of standardized testing set by No Child Left Behind. Following the 2010-11 year, the school, which is also a magnet school for fine and performing arts, was one of 28 throughout the city in danger of being shut down due to low enrollment and poor performance.

“Central is one of the roughest high schools in the city,” said Central English teacher Sadie Stockdale. “Most of the kids have never been given the tools they need to believe that they can be successful in life. They come from low-income homes and are involved with gangs. They believe prison is more of a reality than college.”

Central’s atmosphere and historically low student performance rates seem to have a direct correlation with high teacher turnover rates and a lack of adequate leadership from the district, which allowed Hesston students to see first-hand the effects of education inequality.

“The day was an eye-opening experience,” said freshman Bonita Garber of Bainbridge, Pa. “The level of inequality in education because of economic status is mind blowing. No one ever believed these students could make anything of themselves, so they don’t believe it either.”

Several of the teachers at Central, including Stockdale, work through Teach for America, a national organization that places teachers in impoverished areas with the belief that all students – regardless of race or economic status – deserve a high quality education. Teach for America educators join the program as recent college graduates and typically display strong leadership potential. King taught first grade for three years in Phoenix, Ariz., with Teach for America before joining the Hesston faculty for the 2011-12 year.

Teach for America states that only eight percent of kids growing up in low-income communities graduate from college by age 24. Stockdale and her colleagues work hard at Central to change the perceptions students have of themselves.

“High expectations mean a lot to kids,” Stockdale told Hesston students. “Meeting them where they are at instead of giving up when they don’t quite make it and knowing how to manage your classroom are the two biggest attributes a successful teacher can have.”

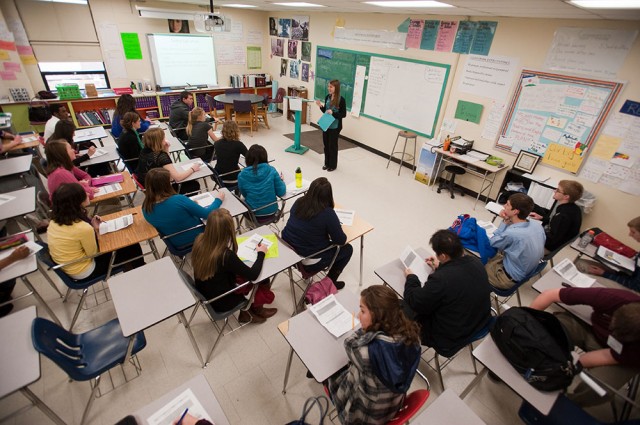

Hesston students had the opportunity to see classrooms and teachers in action as well as put their own skills to work by participating in the action. They spent the day observing in classrooms, doing class presentations about preparing for college and working in small groups with the high school students to review the standardized test objectives that need the most improvement.

“Teachers must develop diversity competencies in order to effectively serve all students,” said King. “This trip was a chance for students to connect theory and research to action.”

For sophomore Brocia Beachy of Wolcottville, Ind., the day was glimpse into what she might be able to expect as she moves on from Hesston following graduation in May. Beachy plans to spend next year gaining more experience in diverse and low economic areas by volunteering with the Hopi Mission School on the Hopi Reservation in Kykotsmovi, Ariz.

“This year, Marissa and my education classes have helped me discover a passion for teaching and how much I care about kids,” said Beachy. “Being at Central made it evident to me that it makes a big difference when teachers care about their students. It was interesting to see different teaching styles and how students respond to them.”

Central teachers thought the experience was good for their students as well as the college students.

“It is good for the kids to get one-on-one interaction with college students,” said English teacher Matt Gress. “It gives them a chance to see what college could be like and hopefully encourage them toward that path as well.”

Despite some initial concerns from the college students about knowing how to engage the students, they came away with a greater understanding of the struggles that are a reality for so many schools, teachers and students in urban and low-income areas throughout the country.

For Beachy, it was added fuel to serve where she is most needed.

“I want to make a difference for kids wherever I might end up,” she said. “I don’t want to just go where it is easy and always comfortable.”